Quickly access the new cost of lead time calculator.

- Long, cross-border supply chains usually increase the lead time between when an order is placed and when the product is received – leading to increased inventory costs.

- Inventory costs due to long lead times often add 20-30% to product costs. These additional inventory costs often outweigh the benefits of offshoring – even without considering other hidden costs of far-flung supply chains.

- The expected mismatch cost arising from a long lead time between ordering product and knowing the final market demand for that product needs to be considered when comparing unit costs. An offshoring supplier with low direct costs may seem initially compelling before considering the cost of overstocks or stockouts, but a far-flung supply chain will often turn out to cost more than responsive local production.

- The Cost Differential Frontier available from the University of Lausanne makes it possible to estimate the expected mismatch cost so that it can be included in deciding whether to produce locally. The tool shows that the cost offered by a supplier offering a long lead time needs to be over 25% cheaper to cover moderate mismatch costs. Alternatively, the tool shows that it is worth paying a premium of over 35% to eliminate a very long lead time.

Firms hold inventory to meet short-term demand surges and buffer against delayed or defective deliveries. Having a far-flung supply chain increases the risks of these contingencies, thus requiring more inventory. According to The Economist, companies importing from abroad may have to hold up to 100 days of inventory in the United States. Authors of another academic study calculated that, when companies in their dataset increased the international share of their supply chain by 10 percent, it corresponded to an average increase of 8.8 percent in their inventory investment costs. This drives up not only the cost of acquiring the larger inventory of goods but the carrying costs as well.

A key reason why inventory rises with off-shoring is that the lead time between ordering and receiving components increases.

Valuing Lead Time

Extending the supply chain to include offshore suppliers usually requires managers to decide how much to produce or order before they have a complete picture of the demand for their product. A firm deciding about what will be produced before observing demand, however, faces two types of risk: overstocking and stockouts. Overstocking is costly because it results in higher inventory carrying costs, the risk of products going obsolete, and losses from selling off excess inventory at a salvage or markdown price. On the other end of the spectrum, stockouts result in lost sales, angry customers and vulnerability to competitors. When comparing suppliers based on the decision lead time, the mismatch costs associated with potential overstocking and stockouts often shows the more responsive supplier to be surprisingly competitive.

This principle is illustrated by the experience of K’NEX Brands, a Pennsylvania-based toy manufacturer that reshored 90% of its production to the United States. Local production allowed K’NEX to be much more responsive in the face of often volatile demand. Because they produce closer to their customers, K’NEX is able to wait longer before making a decision about much to produce. Making more real-time decisions about production has allowed K’NEX to reduce the mismatch costs associated with overstocking, and they have discovered that local production is 19% cheaper than producing in China.

Managers have been aware that extending their supply chain – leading to substantial increases in lead time – increases mismatch costs, but they have not had tools to quantify these costs. In other words, they have not been able to put a dollar value on how much cheaper their offshore suppliers need to be in order to offset the added uncertainty and risk of manufacturing far away from markets and R&D.

Innovative work[i] from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland uses quantitative finance to provide two tools that make such calculations relatively straightforward: the Cost Differential Frontier (CDF) and Cost Premium Frontier (CPF). The CDF is designed to help firms understand the increased costs associated with manufacturing far away from their customers, while the CPF uses the same logic in reverse to help companies estimate the value they can achieve by moving production closer to their final market. To help users get started with the tools, the University of Lausanne created a short video guide.

The key result of the analysis is that these hidden inventory mismatch costs often exceed the benefits of offshoring even before other risks associated with extending the supply chain are considered. As we extend the supply chain to work with distant suppliers, the demand forecast must include substantially more variation. Below is an example of how the tools work.

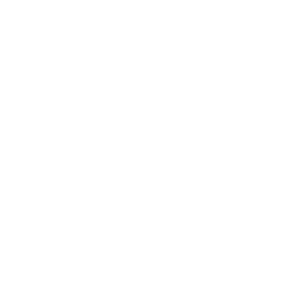

Let’s suppose that a company needs to decide what to order from a distant supplier four months before they know exactly how much their customers want. Using data from a real-life consumer good company, let’s estimate the sales price of the product at $100, with a make-to-order cost from a local supplier of $44 and a salvage price of $20 for unsold product. (These numbers have been invented for the purpose of this example, but their value relative to each other reflects the actual costs and revenues of the company.)

We can get an idea of the demand volatility from our intuition about how much demand varies over time. The company estimated that a typical peak in demand tends to be double their median demand and that these peaks tend to occur 2 weeks out of 50. A calculator built into the CDF allows us to transform that intuition into an estimate that demand volatility is around 40%. The results of the CDF calculation are shown below.

As you can see, the CDF predicts that a 22% cost reduction is necessary to compensate for the increase in risk associated with a long lead time. However, the actual cost differential offered by the long-lead-time producer, in this case, was considerably less than 22%.

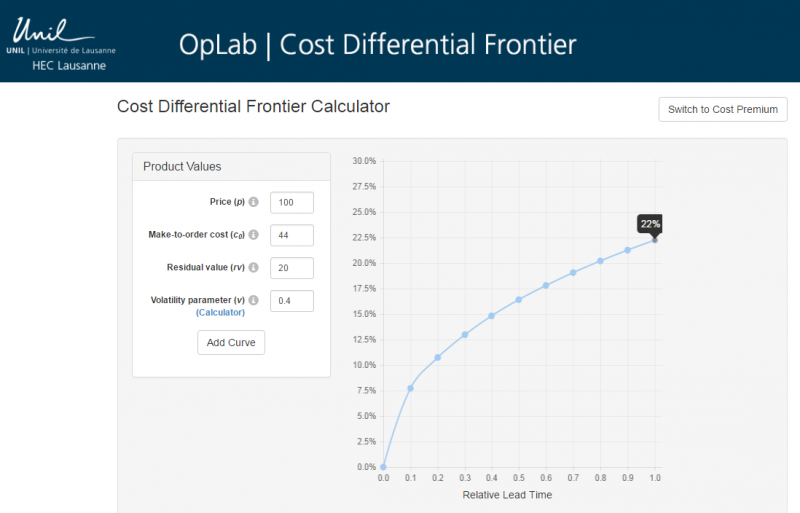

The CPF reverses this logic to help a firm understand the cost savings associated with moving production closer to customers. Using the same parameters as before, let’s consider a case where the quoted cost from the long-lead-time producer is $40, for a cost differential of around 10% compared to the $44 price from a local supplier. In this case, we can use the CPF to calculate the cost premium that the company should be willing to pay to a more responsive local producer. As we see in the figure below, the CPF tells us that it is worth paying a premium of 28%, or over $50, to eliminate exposure to demand volatility!

What Factors Make Reshoring Attractive?

The tool shows that the following factors are particularly important:

- Large or frequent unexpected spikes in demand

- Low salvage value compared to full selling price

- Local supplier is able to quickly make to order. The steep slope of the curve near a relative lead time of zero shows that getting very close to zero lead time is especially valuable.

Note that these factors are not confined to particular industries, and that on-shoring even labor-intensive production may be profitable if demand volatility is high enough, as in much of the apparel industry.

Carrying Costs

The CDF tool discussed above shows that long lead times add costs by increasing required production, including of products that will most likely be sold at a steep discount. Holding this additional inventory also adds expense, due to “inventory carrying costs”.

Inventory carrying costs include a myriad of factors:

- Warehouse space

- Administrative management costs

- Scrap, sorting and rework

- Obsolescence and deterioration

- Insurance

- Taxes

- Cost of capital

The last of these factors, in particular, can be easily overlooked. The cost of inventory is not solely determined by the direct expenses associated with storing, managing and maintaining the goods, but also by the opportunity costs that arise when money is tied up. Goods represent a store of value; keeping resources tied up in products or components that are not being utilized or sold immediately restricts a company's overall cash flow and may reduce the amount of liquid capital available. Inventory management requires a careful balancing of all these costs against the benefits of having more goods or inputs available on demand.

As a rough rule of thumb, many sources, including the Reshoring Initiative, use 25 percent of a product's unit price as an estimate of annual carrying costs per unit. However, the actual number for any specific company, product or component may be considerably higher.

In addition to the costs of carrying inventory onshore in the United States, companies must also consider the carrying costs of inventory in transit. It is easy to overlook the carrying costs associated with these products because they are not sitting in a warehouse, but they form part of a company's overall inventory and represent money that is tied up in goods. They also require the payment of insurance, consideration of the ultimate need for scrap and rework, and other factors. Companies must be mindful not to disregard the cost of carrying inventory that has not yet arrived at its final destination, especially given the amount of time this inventory will spend in transit and the associated financing costs.

Firms are trying to reduce their inventory costs. Importing from China to the United States may require a company to hold 100 days of inventory. That burden can be reduced if the goods are made nearer to home. In fact, Mexico is increasingly attracting production destined for the United States that would have formerly gone to China. Average pay for Mexican manufacturing workers is now only slightly higher than for Chinese ones, and the time it takes for goods to travel to North America is measured in days rather than months.

Supply Chain Flexibility

In competitive markets, being the first to offer a new product secures important market share before similar products are offered by competitors. Sourcing goods close to their final markets allows for new products to have smaller production and transit cycles. For some products, it also allows firms to design, modify and adjust products almost at will, while also enabling them to scale production according to demand and to avoid waste. Longer supply chains can decrease this flexibility. Companies can expect to wait a month or more between the time components are shipped from foreign factories and the time they arrive in the United States. For high-value consumer items, this is often an uncompetitive strategy. According to one study, each day a desired consumer product is stuck in transit is equivalent to an ad-valorem tariff of 0.6 to 2.3 percent. This means that domestic competitors with even moderately more expensive production costs can win market share by bringing products to market faster. Indeed, a 2014 study by Colliers International found that 82 percent of companies consider proximity to customers important in manufacturing, while a 2012 survey conducted by MIT's Forum for Supply Chain Innovation found that time-to-market was a major factor driving reshoring decisions.

On the other hand, many companies may prefer geographic diversification over concentration. In 2011, floods in Thailand and the earthquake in Japan closed many factories. Companies with geographically diversified facilities can end up in considerably better shape than those concentrated in one place. A challenge that companies should keep in mind while diversifying is that it is important to understand the entire supply chain. In the case of the Japanese earthquake-tsunami, many automakers simply assumed that their supply chains were spread out geographically. They discovered, however, that their supply chains were diamond-shaped, with mid-tier suppliers all relying on the same downstream sub-suppliers (who were, in turn, simply invisible to the large companies at the top of the supply chain).

Conclusion

Inventory and lead time costs are important and are reflected in firm’s location decisions. According to a 2013 study by Accenture, about four in ten manufacturers surveyed reported that they had relocated production facilities to new locations since 2011. Of those firms, nearly one-third listed reduced transportation costs as one of their top three reasons. One quarter cited increased responsiveness or reduced lead time. Nearly half of all firms surveyed had started new operations since 2011, and one in four cited reduced transportation costs and lead time as top-three factors.

Lean inventory management and supply chain flexibility have become key components of the modern business environment. Companies choosing to produce or source abroad must carefully consider the costs of increased inventory and the risks associated with a longer supply chain

[i] This article was published in the Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 32, Suzanne de Treville, et. al., "Valuing lead time," pp. 337-346, Copyright Elsevier (2014). The Journal of Operations Management may be accessed online at http://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-operations-management.